As soon as I published the last newsletter, I remembered a million other books I could have talked about. Isn’t that how it always goes? I thought about sending out an addendum, but as time moved forward, I figured why not let these books be the jumping off point for another missive about books. Let’s start again by talking about…

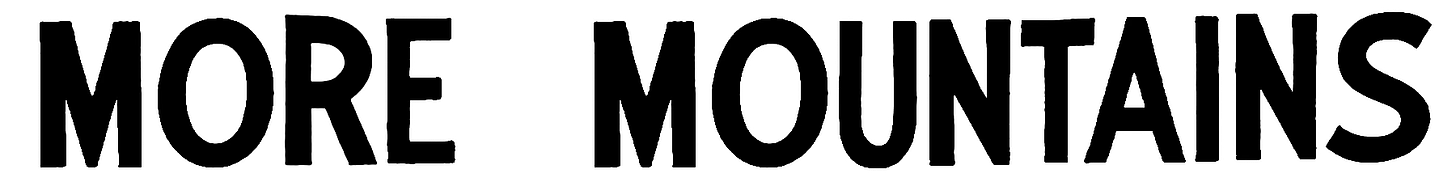

It is truly idiotic that this wasn’t one of the first books I grabbed when I wanted to talk about the mountains of California. There it all is! Then again, Muir doesn’t always land for me in the same way that McPhee does. Sometimes I feel like he’s just recounting details from his diary, instead of weaving them cohesively together.

I like this copy a lot (once I knew this design existed, I found it later that week at a thrift store…you gotta put the vibes out into the world)—I am not a fan of a lot of the modern designs of his books. Like he’s some stoic mountain man, an untouchable saint of nature. This one is so neutral. It’s less about the celebration of Muir as a legendary figure and more about the mountains as a landscape. Good. Exactly as it should be.

This book is an excellent segue from mountains into our next subject, because it is the beginning of

in California, and it contains one of my favorite chapters about it.1 After traipsing up and down rocky mountains, through valleys, over dripping glaciers, the final chapter, “The Bee-Pastures” marks a refreshing shift from the rugged attitude of the rest of the book. You can tell Muir really delighted in the floriated patches of the state:

“When California was wild, it was one sweet bee-garden throughout its entire length, north and south, and all the way across from the snowy Sierra to the ocean. […] during the months of March, April, and May, [it] was one smooth, continuous bed of honey-bloom, so marvelously rich that, in walking from one end of it to the other, a distance of more than 400 miles, your foot would press about a hundred flowers at every step.”

He traverses the big open valleys, the foothills, the forests, and also takes digs at people settling in wild areas, searching for gold, pasturing their sheep. He talks about the business of owning beehives and the settlements cropping up, but each time it’s interrupted by his utter giddiness at the thrill of being outdoors while it’s in full bloom:

“The blood of the plants throbbing beneath the life-giving sunshine seems to be heard and felt. Plant growth goes on before our eyes, and every tree in the woods, and every bush and flower is seen as a hive of restless industry. The deeps of the sky are mottled with singing wings of every tone and color; clouds of brilliant chrysididae dancing and swirling in exquisite rhythm, golden-barred vespidae, dragon-flies, butterflies, grating cicadas, and jolly, rattling grasshoppers, fairly enameling the light.”

There is….a force (?) that comes from the Great Outdoors sometimes. I think John Muir was tuned into its wavelength here. It beckoned to him and he had no choice but give himself up to its magnetism. I also maintain that John Steinbeck felt this pull as well (I promise not every book I read is by someone named John), and you feel it in the beginning of East of Eden2:

“The Salinas Valley is in Northern California. It is a long narrow swale between two ranges of mountains, and the Salinas River winds and twists up the center until it falls at last into Monterey Bay. I remember my childhood names for grasses and secret flowers. I remember where a toad may live and what time the birds awaken in the summer—and what trees and seasons smelled like—how people looked and walked and smelled even.”

This first chapter keeps coming back to wildflowers. “Every petal of blue lupin is edged with white, so that a field of lupins is more blue than you can imagine.” The poppies too, are “of a burning color—not orange, not gold, but if pure gold were liquid and could raise a cream, that golden cream might be like the color of poppies.”3 There are smells of maidenhair ferns in the shade of oaks, and grass that turns yellow and red as it dries. There were “harebells, tiny lanterns, cream white and almost sinful looking, and these were so rare and magical that a child, finding one, felt singled out and special all day long.”

To pay attention like that to a place, year after year, shows devotion and reverence in equal measure. It’s easy to feel this in the abundant sunshine of California, but it’s not exclusive to this state (I’m thinking of Aldo Leopold in Sauk County, Wisconsin, and I’m certain there are others that I’ll think of the minute I publish this newsletter), and it’s admirable to be able to find this kinship between your body and the place it’s in. It doesn’t need to be the wilderness, it’s still there even if you’re in a city—the trees, the sunshine, the clouds can all be watched closely.

I understand “the pull” very well. When this time of year rolls around I am overcome with, for lack of a better phrase, spring fever. I can hardly bear to be indoors when I know that at any second, another California poppy in the backyard might push off its wizards cap and open its petals to the sun. I might miss a ladybug hunting for aphids, the dusty smell of pollen from the verbena catching the breeze, a new bird in the bird bath, a lizard catching a grasshopper. Finally at a certain point the pull becomes too intense, and I give in. I watch nothing. I watch everything. It fills my cup up again in a way that only it can. It’s bees on the rosemary, flower wasps hovering in their strange figure eight patterns, the praying mantis eggs on the olive tree that could, at any moment, hatch into any number of perfectly miniaturized praying mantises! How could I be bothered to sit at my computer when that is happening just on the other side of my wall?

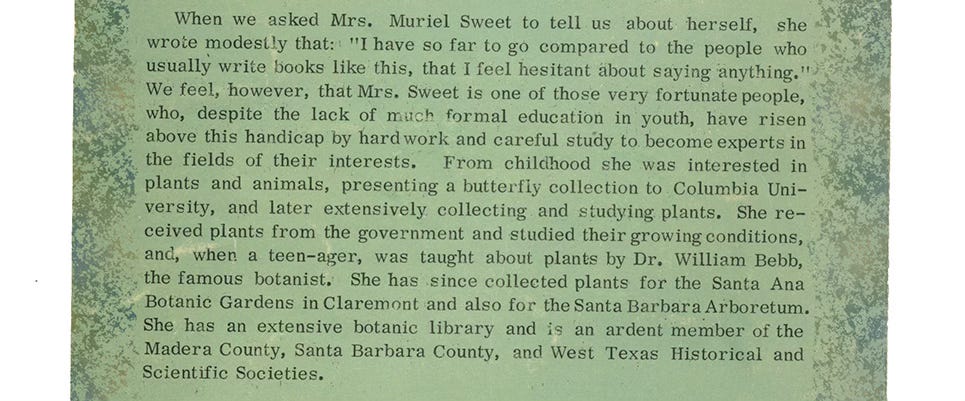

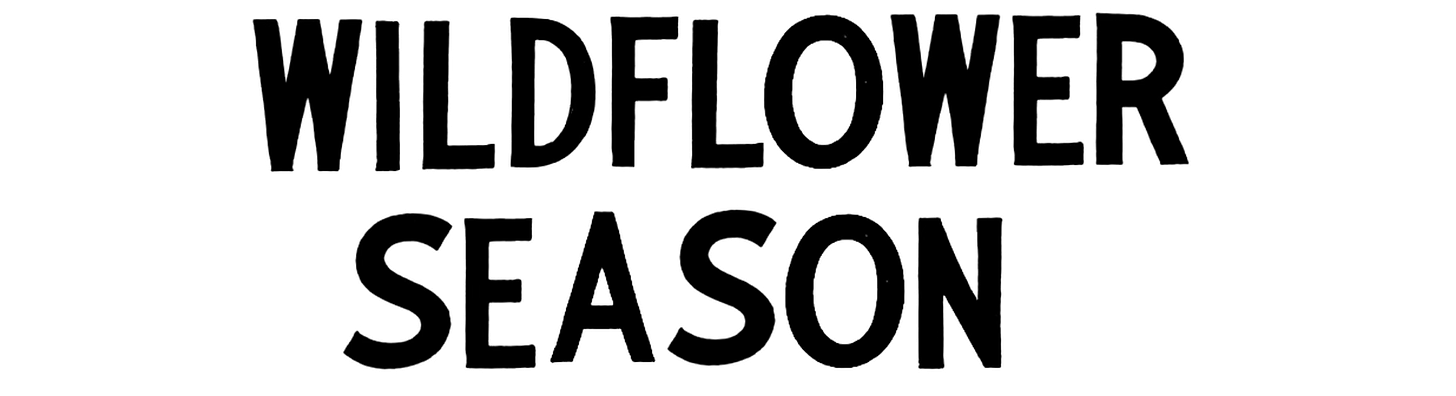

My shelves are graced, of course, by several scientific field guides—vintage Peterson ones that are good illustration reference (you know them, the blue covers), and the modern ones from the University of California. Though over the years I’ve come across more and more guides from people that might not have the scientific credentials per se but still wrote useful pieces about where they were. You could call them “amateur” but they’re really anything but. Here is one I acquired a few months ago:

If ever there was a prime example of how to explain imposter syndrome, it is this paragraph on the back, about the author, Muriel Sweet:

After all, the origin of the word amateur is from the Latin amare—to love. Muriel Sweet was an amateur in the literal sense of the word’s history. She loved the natural world from a young age. If you don’t love something, how can you become an expert anyways?

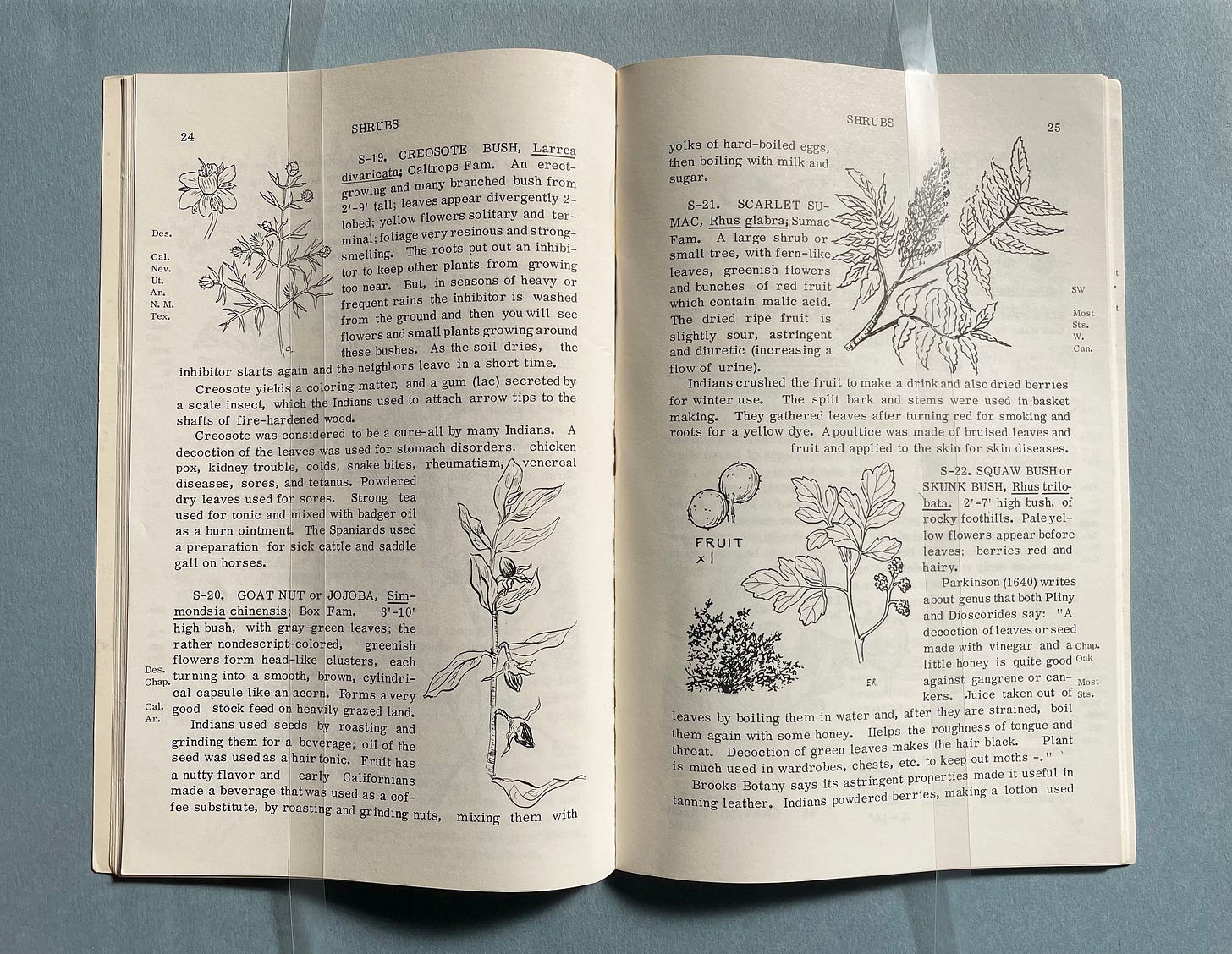

The layout of this book is a little chaotic, almost useless in the field unless you knew exactly what you were already looking for already:

It does have a warmth about it that only something of a pre-computer era can manage. It fills up the pages a little too much, but if you read through this book at least once (it’s slim, no more than a quarter of an inch), you would completely understand how it functions. And for a book about what you can forage, you should read it more than once. It could be the difference between life and death (or diarrhea!).

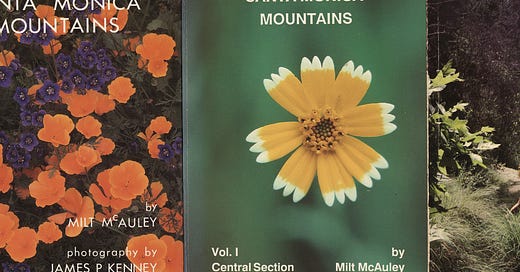

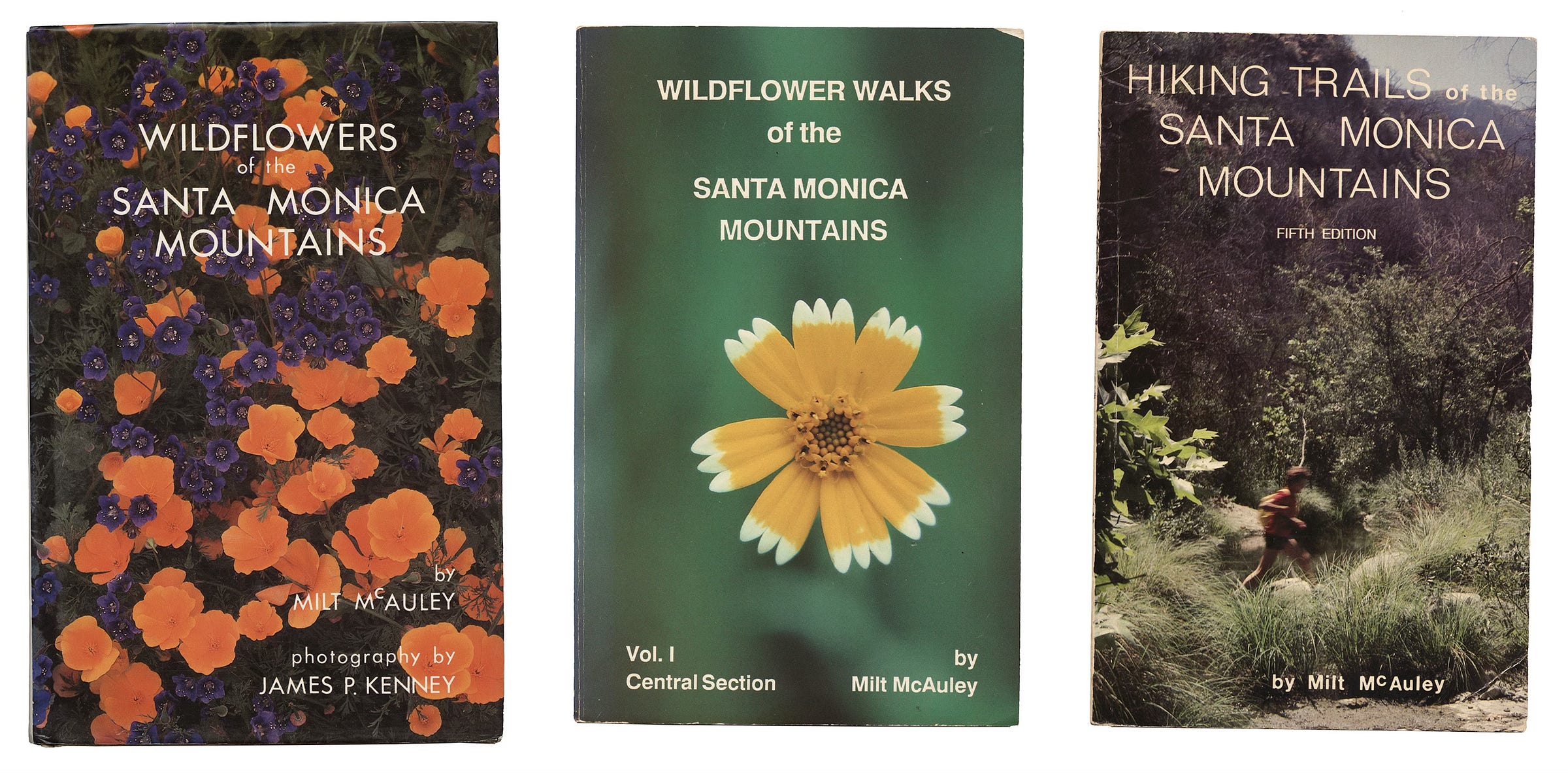

There are also books on my shelf by Milt McAuley, whose muse was the Santa Monica Mountains, and who walked the line between amateur and expert just as deftly:

He first published the book of hiking trails in the early 80’s. In his obituary in the LA Times in 2008, they quote him saying, “There was no adequate hiking guide at the time. I made the statement that you would think an average person could do a better job than this. Someone said, ‘Prove it.’ So I did.” The book was rejected by a publisher so he published it himself. In that regard, it’s also amateur, but I think these regional nature guides are a good example of how blurry the line between amateur and professional can be. They’re not doctored up to look like something they’re not, and they can’t hide behind “good design” if the bulk of their content isn’t useful. You can’t build something solid without a good foundation.4 Plus he was, as evidenced by the extensive bibliography in the back of Hiking Trails, adding more information to what already existed.

He walked through these mountains at least every week, and that simple action was the foundation for him to become deeply invested in them.5 Despite knowing that land needs to be protected, he also understood that people need to experience it in order to care about it: “If you didn’t build a trail and invite people in, someone would come along and subdivide the land. To preserve parkland, you need access to it.”

The spine on Wildflowers of the Santa Monica Mountains feels like the giveaway that these were self-published (though he and his wife founded their own publishing company to produce these—the line between amateur and professional gets blurrier).

I’m 90% positive this was laid out with Letraset. It’s perfectly wobbly, and I love that the “c” on McAuley is moved up like that, a little bit of the human-hand showing through on an otherwise clean and “professional” looking layout.

Wildflowers is a particular favorite for how simply he doles out information: how to use the book, the history of fire in the mountains, or the different plant communities one might encounter. The scientific information never feels stodgy and weighed down. It’s there to lend clarity to a trough of knowledge that can otherwise feel impenetrable if you didn’t study science. He’ll show you what you need to know with drawings or photos, and describe the plants as straightforwardly as possible, but you can always tell that there is no better way to know these things than to see them up close. If ever there was an invitation to do just that, this is it:

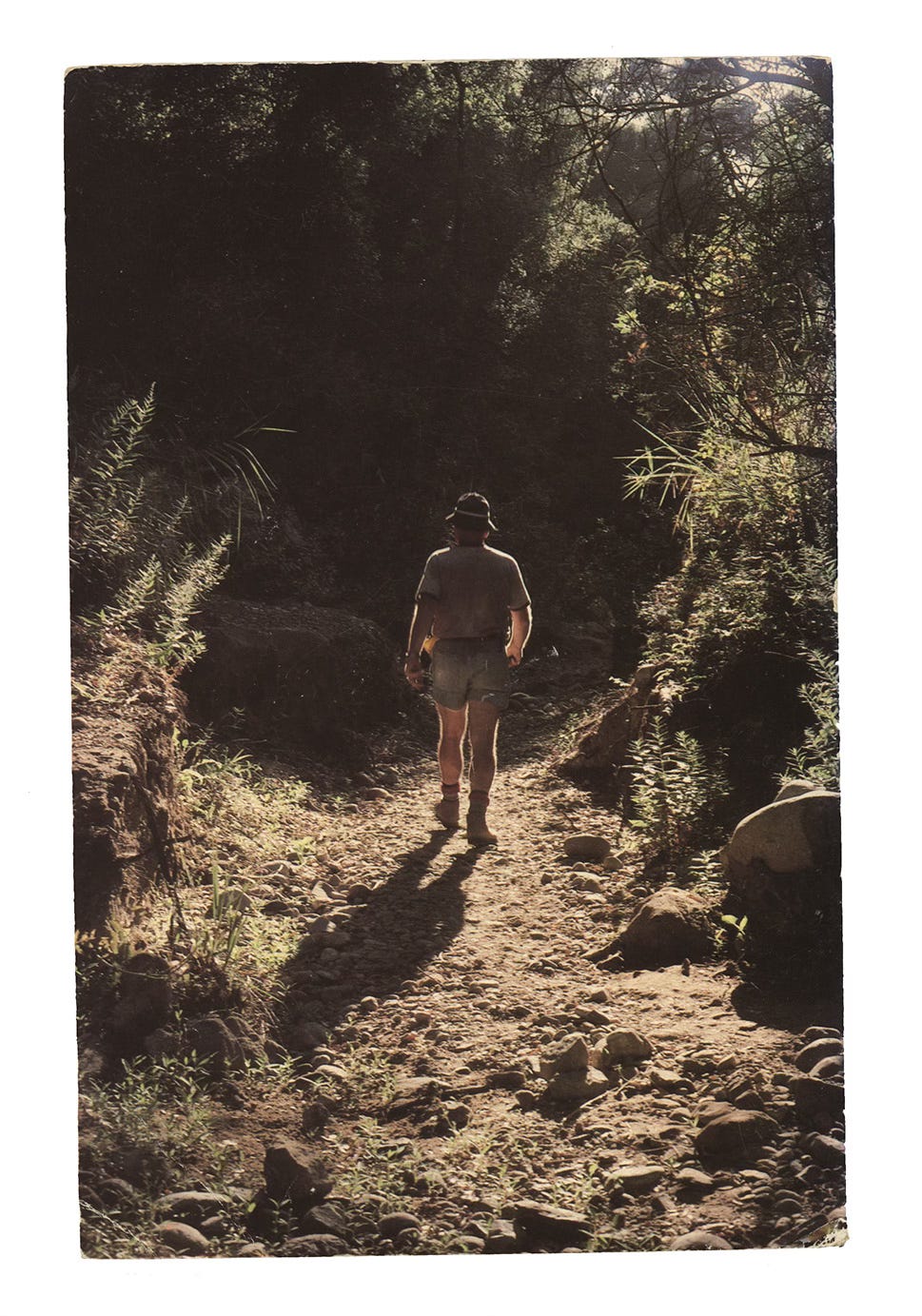

This the back cover on all of his books that I own. Save for one book with a barcode on top, there is never any additional text. Who cares how many degrees this person has, how many awards and accolades they’ve accumulated—here they are, comfortable, confident, courteous in the place they’re writing about…in the place they know so much about. It says so much more than a photo of them smiling with a blurb underneath it ever could. Even from this photo, you feel an inherent trust in him, that he’ll lead you around this bend to whatever magnificent thing lies beyond.

Amateur for sure.

Books featured this month came from: thrift stores, used book stores, flea markets, birthday gifts.

The book I reviewed in issue 2 of Bugue, which I won’t mention by name here, is also good California wildflower reading.

East of Eden also exudes a pull of its own—I first read this book in Chicago (on the bus, train, or in the park) and never have so many strangers talked to me. Not one of them wanted to interrupt me too much though—it was always as they were exiting the bus or train, a quick tap on the shoulder to blurt out “I love that book, I hope you like it” before hopping off and continuing on their way. One person even showed me the first tattoo they ever got: the Hebrew word timshel.

Here’s another plug for Bugue, where I also talk about the idea of colors of the natural world in a piece about “popular chromatic nomenclature”

You can’t make chicken salad out of chicken shit, as a teacher of mine once said.

He was one of the original hikers who plotted the Backbone Trail, which runs the length of the mountains. You can still hike this trail, and there is an upcoming week-long trip led by the Santa Monica Mountains Trails Council—a trip Milt himself used to lead.

May I suggest: Anthology of Turquoise by Ellen Meloy <3

And I have never read any Steinbeck (don't tell anyone), I think I'd better.

Wow that East of Eden cover!!