Last year, like many people it seems, I decided to change my reading habits. In fact, this change was a shift back into a habit that I had lost over the years. A habit I can pinpoint to one thing: moving to LA1.

I have always been a reader, a good reader, a fast reader, and as any reader of any ability will tell you: reading expands your mind. Not even in, like, an information-building/self-improvement way, I’m talking just in elasticity. The ways that our thinking can move and interpret and admire and everything else can only be improved by reading. Like any muscle, we need to exercise our brains in order to keep them fit. Reading is good for us, even if it’s sometimes painful to do it! I did push ups the other day and that sucked, but I know it’s good for my shoulders, arms, and chest, so I powered through. Last year, reading a physical book felt like a multi-vitamin in a world where the internet felt like a handful of caffeine pills choked down without water.

Looking back at last year’s list, it’s mostly fiction of many different genres, and non-fiction about nature. Thirty-four books in total. I asked friends for recommendations, and then spent the year scouring stores to find used copies of them2. I looked at the authors I already liked and tried to find the books I was missing by them. Sometimes I just read the first page of a book that looked interesting (turns out judging them by their covers kind of works?) and if I was hooked, bought it. Reading in my free time started to feel like an anti-algorithm. Or the opposite of an algorithm. The antidote to that omnipresent unseen force that had spent years directing my attention and taste this way and that. My reading list was not determined by what other people my age and gender and in my vicinity were reading, it was determined by what my friends and family were reading, or what fate could drop in my lap at any given moment. Sometimes this meant crazy jumps from author to author, subject to subject, but other times it felt too good to be true: while reading H is for Hawk, and stumbling across a vintage copy of The Goshawk at the thrift store. Kismet!

I have found myself revisiting my book shelves more as a physical space. Like a conspiracy theorist tying red string across a cork board of photos and maps, I’ve started to find books speaking to each other from their different sections. Language in a pruning manual reads like poetry. A poem reminds me of a painting I saw in a monograph. That painting reminds me of a photo in a nature guide. The divide between the sections of fiction/non-fiction/poetry becomes less clear the more I read, the more I acquire. There is non-fiction as exciting as a thriller, and fiction as boring as a math textbook. Each completes a little part of my knowledge gap in some way. Each will stretch my mind in new ways that it hasn’t been stretched before, and in old ways that it has forgotten it could move. And, like most readers know, revisiting a book years later often brings to light a new interpretation. Years of living can give an old book new meaning.

I want to write about some of these little groupings of books, both of their content, their design, and their physicality in the world. It will be a mix of a lot of it—art books, fiction, non-fiction, nature guides, etc. I don’t want this to become a place of recommendation where anyone feels obligated to buy the things I am talking about, though (but if a book catches your fancy and you read it, so much the better). There is nothing worse than a book bought purely as a decorative object3 and I guess this is more of an exercise in looking at what I already own, rather than wanting for more because it’s “in” or because it would look good on my shelf/coffee table. If I’m going to continue to preach about how bad social media is (on social media, woof) I should at least be vigorously trying to hawk the joys of not structuring your life around it. And yet, I’m not going to show you my book shelves. Maybe I’ll describe them in more detail later on. Because that’s another cool thing that reading can do: take words and form an image that you “see” in your brain but you don’t actually see with your eyes. That’s pure magic. And maybe a little mystery could be good.

Without further ado, let’s talk a little about…

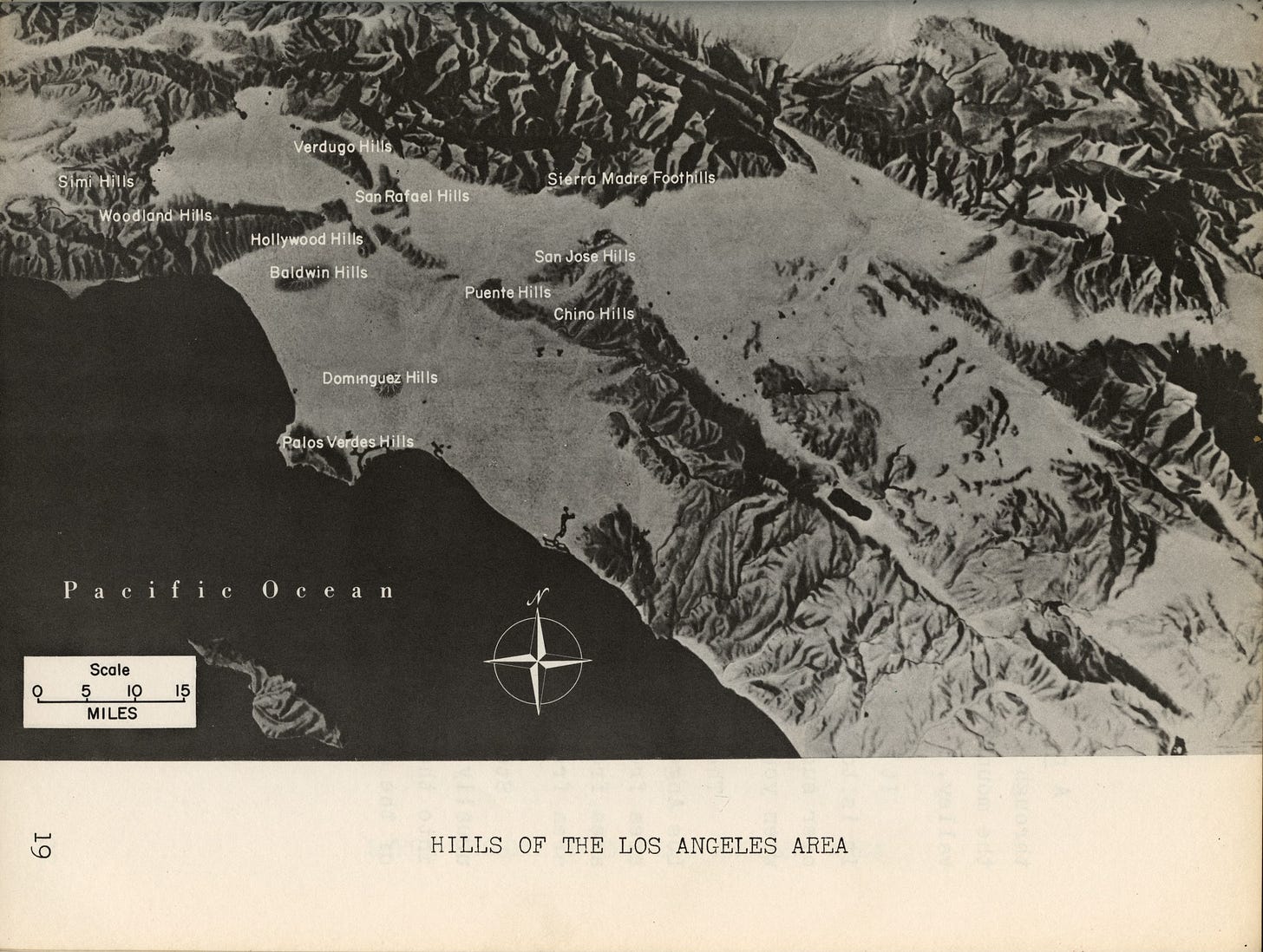

California is full of ‘em. It’s hard to go anywhere in the state without being on a mountain or near a mountain, or to see mountains in the distance. Clay and I have the habit of calling them “doinks” after Jenny Slate’s book Little Weirds (where she says earth is full of “dollops and doinks” of mountains.) Having grown up in a flat place (Minnesota) and then having spent about a decade in an even flatter place (Illinois), mountains are a new-ish consideration to me. For years after we moved here, I couldn’t figure out what the mountains ranges were called. Google searches came up with images that were impossible for me to decipher. They either had way too much information or not enough information. I lamented, out loud, that I just want a simple map with the mountain ranges labeled, and one day Clay delivered just that with this little text book from 1963 that he more or less pulled out of a dumpster.

It should be no surprise that often the best info is also the simplest. And this geography book for third graders is perfect. A simple notion is presented in the beginning that seems straight-forward, but is, when you think about it, a beautiful invitation to think about the interconnectedness of the world:

I pulled this book from the shelf in the days after the fires started. It was frustrating to hear so many people who don’t live here talk about this place like they were experts. I am no expert either, and this book does not make me an expert, but I had a decent grasp at the lay of the land, at fire behavior, at how much of an anomaly the winds were just from living here. I appreciated the friend who texted, saying “I don’t understand the geography of LA. Are you okay?” I hardly understand it either. But here with this book, I have information about the literal foundation of what LA is built on (which arguably, extends from geography into geology; more on that in a second).

LA is HUGE. Most of it’s in the basin between five mountain ranges, and the mountains really shape our weather and our vegetation. “A mountain is land that is very much higher than the land around it,” as the book says, and it is the understatement of the century. It sounds like it’s meant to keep us calm and not panic if we encounter a mountain. If you find land very much higher than the land you are standing on, remain calm, it’s only a mountain. It might be faster to walk around it than to walk over it but either way it will take a lot of time. It is moving, but so slowly that you won’t notice. (Unless, one day, you do.4) If I look out my windows I can see the Santa Monica Mountains to the west, the San Gabriels to the north and east. If I climb up the mountains on a clear day, I can see the ocean.

The book smartly uses the same map with different information marked on it (this is likely a combination of cost-saving & just how things were done before computers). Here are the mountain ranges, here are the hills, the foothills, the passes, the valleys, the basins, the lakes, the rivers, the bays, the peninsulas, and the tar pits, shown on the same map image and bound together in a book that is so simple, a third grader could understand it.

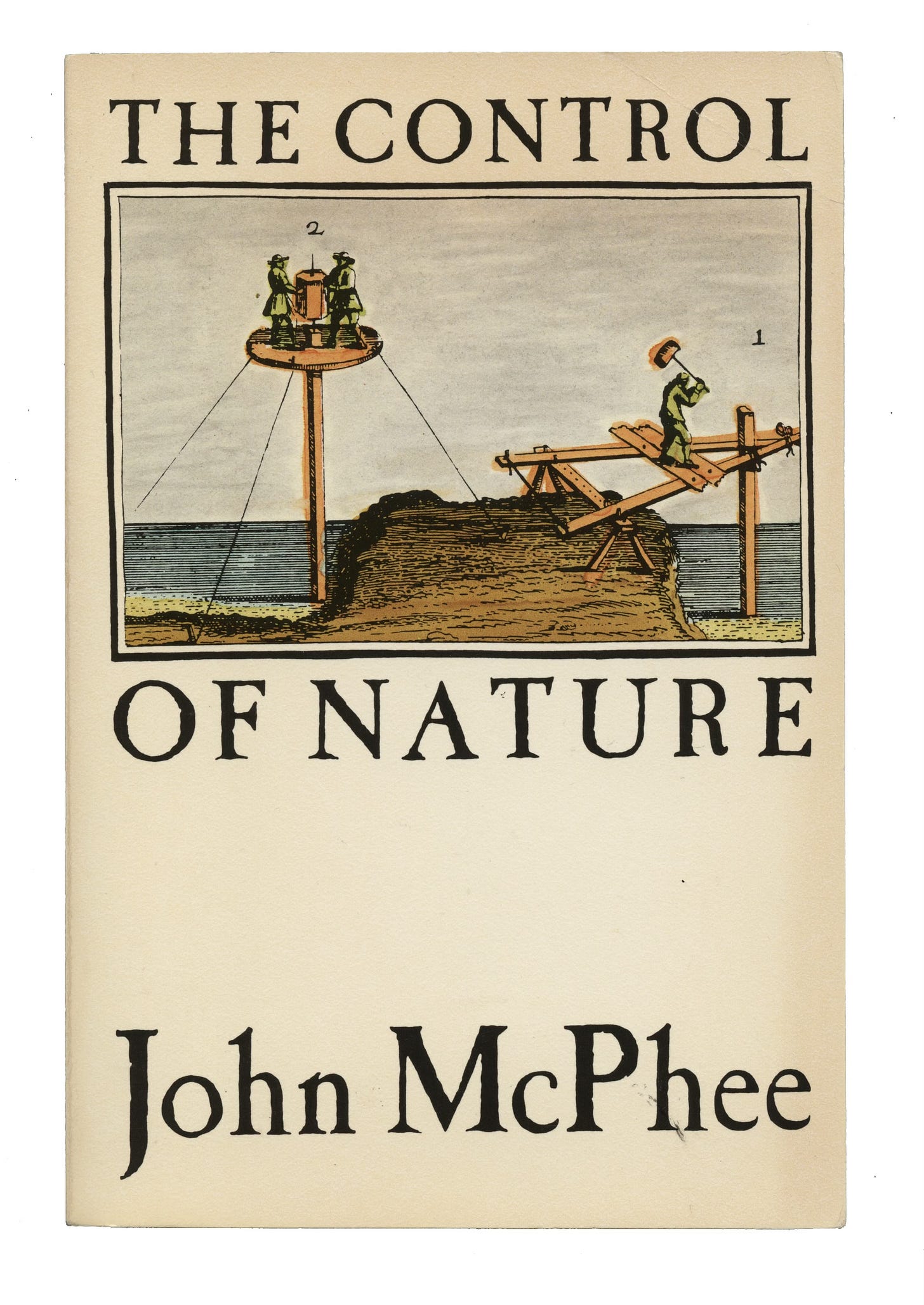

Now that the winter rains are finally, finally, starting to fall in Los Angeles, I’m brought back to a book by John McPhee titled The Control of Nature.

There are three sections in this book, which are all about humans trying to out-engineer the force of nature. There are the levees in Louisiana (floods), hoses and water (?) in Iceland (lava), and the mountains and river in Los Angeles (debris flows). “Los Angeles Against the Mountains” is simultaneously engaging and terrifying. Most of John McPhee’s writing about California is. Being scared is no reason to not engage, though, especially what with the giant burn scars so close to populated areas, and rains falling, it’s an important reminder that danger doesn’t end once the fire is out. And that humans can only control so much. They have dug basins to catch boulders that cascade down mountains after various weather and geological events, but no system is perfect, and everything has weak points. Whether that be in their engineering or in their bureaucracy. Then again, one can’t live life without a certain amount of risk. Nature will always have a certain level of unpredictability. A lot of people who live in California know that these events are terrifying, but this state is jaw-droppingly gorgeous during all those days, weeks, months, years between. We are quick to forgive it and to forget.

I want to pivot for a minute to talk about the design of this book. This is the paperback version, and I think this is a printers mistake, but it’s my favorite back of a book ever:

Is it just me or are modern book covers full of too much shit? I’m not sure when this began, but there are too many accolades and blurbs all over the fronts and backs of books these days. It’s distracting, and more importantly, it’s muddy. Totally acceptable design gets mucked up by praise for the book, by previous books the author has written, and sometimes by overly long subtitles.

I don’t think McPhee’s books are the pinnacle of great design, but many of them are from the tail-end of an era that didn’t use computers to design the way we do now. They’re not literal, but they’re also not mysterious, or, like, easter eggs for the super fans. They’re generally good encapsulations of the book’s content and tone. You feel like the designer actually read and understood the book (though realistically they probably didn’t read it). These days so many nature books use old watercolor botanical illustrations on the cover. In general I like these, they’re delightful images, but they’re becoming stale. Seriously, go into a bookstore and tell me how many books about nature don’t have an old-fashioned illustration on them. I imagine they’re probably cheaper to license because the artists aren’t alive anymore. They might even be in the public domain. The Control of Nature might seem like it’s just a generic, antique illustration of engineers building something, but after you’ve read the book, it fits well: who are these goofy old-timey men trying to build something solid on a beach? What will this contraption do? And look at its proximity to the water. Have they not heard the tale of King Canute and the tide? It’s not us against nature, no matter how much we try to control it. It’s us and nature.

Another old drawing (a map, this time) was used for another McPhee book about this state: Assembling California.

It, too, might seem literal, but as you read, you learn what a puzzle the geology of California is. These pieces are not randomly tossed together here, you can see where they join, and they are scattered as though they’ve come apart by a gentle shake, a slight disturbance. Plate Tectonics, as a theory, has only been around since the 60’s, and California is an especially strange place, geologically. Well, if you read some of his other books on geology, everywhere starts to seem strange.5 If the third-grade geology text book gives you the most basic primer on the Los Angeles region, Assembling California is a glorious dive into the deep end of the rocks and the spaces between the rocks that make up this state. I think of John McPhee’s books often because I appreciate that he’s usually writing about the world we are all likely to encounter here in the U.S. He’s not writing books about some geological anomaly halfway around the world—he’s writing about the places we live. Here are our literal foundations. They move in geologic time, and we move at a fast-paced clip, measured by a clock, or a calendar. Sometimes our paces match each other, and we experience geologic time in the form of events like earthquakes. Us and nature.

Let us take a moment to appreciate the end papers from his geology series, which are a timeline in millions of years that is still, after spending so much time with it, impossible for me to wrap my head around. These were drawn by Tom Funk, who I believe was a mostly-mid-century illustrator of magazines and books, and various other things that us freelancers (still) cobble together to make a living. The covers of both these McPhee’s were designed by Cynthia Krupat. If you look closely at the puzzle pieces on Assembling California, you can see that they were cut by hand, likely by Cynthia’s hand, and probably from an actual map which was glued to a piece of paper and then scanned or photographed. There is a subtle shadow around all the puzzle pieces that wouldn’t be there if this was made digitally. It hardly matters, but it somehow imbues a little more spirit into the whole thing. A person made this. A person read this book (maybe) and made this art about it. Well, first a person wrote this book, but before that they drove around the country talking to other people about this idea, and before that these people showed interest in the rocks and began to study them, and before that the rocks moved slowly for millions of years, and before that they were other rocks or maybe lava, and before that they were nothing. Us and nature.

I know this is when the habit fell off because most of my reading time in Chicago came during my daily commute on trains and buses. I could breeze through 1-3 books a week, and in our first years in LA, a car city, I was lucky to read 1-3 a year.

Whenever I do need to buy a new book, though, Skylight Books is my go-to, followed by Vroman’s. The local stores also receive my love and devotion.

Except a shelf of books arranged by the color of their spines? No judgement here, but also a little judgement. How do you find what you’re looking for?

Being a transplant, I haven’t experienced too many earthquakes. I slept through the first one. The second one rattled our front door and I thought it was burglars trying to break in (through the front door in the middle of the day?). The others have moved the ground in ways unimaginable until you feel them—like a sudden drop, like a vigorous shake, like shallow undulating waves—ways that I didn’t know solid earth could move.

John McPhee has actually written five books (and several shorter pieces) about the geology of the United States, and the people who work in it/study it. They’re compiled into one collection called Annals of the Former World, but you can find them individually, and about the following areas: Basin and Range (the American Southwest), In Suspect Terrain (from NY to Indiana), Rising from the Plains (Wyoming), Assembling California, and Crossing the Craton (the Great Plains).

Ooh, another Liana on Substack for me (also a Liana) to follow! This was very interesting to me, since I am a Californian (grew up near the top of "Assembling California" cover between Nevada City and Marysville). However, I do arrange the bookshelf by spine color. It is less about being able to find a *certain* book, and more about the odd juxtaposition of certain books next to each other, and the visual cohesion of the color blocks.

Ohhh thanks for all these words and thinkings Liana! Big fan of Annals... so captivating!